In the galleries: Tension and beauty collide in Michael Sastre’s paintings

By Mark Jenkins November 18, 2016

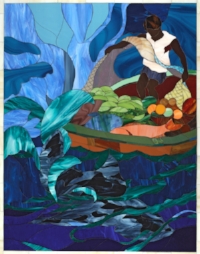

Michael Sastre’s “Jungle Carnival (Spoonbills), 2014, oil on wood panel, 12 by 16 inches. On view through Nov. 20 at Kaplan Gallery, VisArts at Rockville. The artist’s realist oils depict gentle moments of light and color, punctuated by dark and menacing images. (Michael Sastre)

In his realist oils, Michael Sastre depicts pink flamingos, green jungles and everyday life in Caribbean hamlets. Oh, yeah, and drug smuggling. The artist’s VisArts show, “Collision/Collusion: A Personal Underground,” could be a collection of unusually detailed storyboards from a planned narco-thriller, or a collaboration between John James Audubon and cocaine-conspiracy reporter Gary Webb. When the painter includes a drive-in theater in one vignette, the movie on the screen is “Scarface.”

Yet Sastre, who has a studio in Rockville and lives part time in Miami, doesn’t disclose a political or even narrative agenda. In the foreground of his paintings are gentle moments, such as a river baptism or a dog’s nap. The drug-laden aircraft that swoop through these landscapes are as everyday as the birds whose flights mirror the planes’ movements.

The artist has “a very close family connection to the world depicted in his recent work,” a mysterious biographical note reports. But Sastre seems just as interested in the pictures’ settings as in their activities. He carefully renders dense foliage, crimson skies and complex reflections in languid rivers. The show also includes pencil sketches and airplane parts, but it’s most compelling when all of its elements — light and color, scenery and activity, banality and menace — combine in a vision of radiant nature and grubby humanity.

Michael Sastre: Collision/Collusion: A Personal Underground On view through Nov. 20 at Kaplan Gallery, VisArts at Rockville, 155 Gibbs St., Rockville. 301-315-8200. visartscenter.org.